Version 26 February 2017

Recent research has documented the presence of multiple Phytophthora (pronounced: fie-TOF-tho-ra) species in California native plant nurseries, restoration sites, and native landscapes. The interdisciplinary Working Group for Phytophthoras in Native Habitats (calphytos.org) is actively involved in expanding efforts to prevent further spread of these serious plant pathogens, which threaten both rare and common native species in the wild and in cultivated landscapes. The working group includes plant pathologists, restoration ecologists, native plant nursery operators, and federal, state and local agency and district staff.

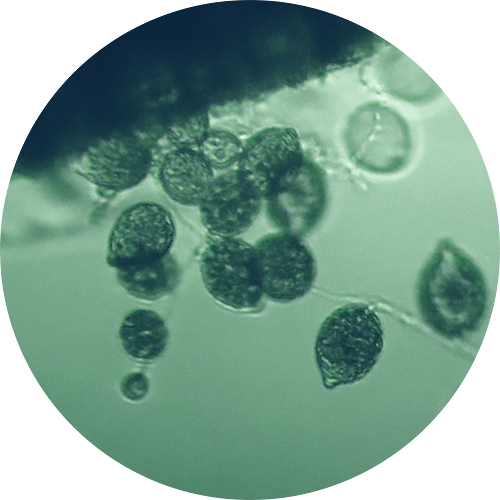

Phytophthora species are microscopic water molds. Previously considered fungi, these microorganisms are now placed in the Stramenopila. They are more closely related to the brown algae than to true fungi. Diseases caused by Phytophthora species include root roots, stem cankers, and blights of fruit and leaves. Host ranges of individual Phytophthora species vary, but some species can infect hundreds of plant species across many plant families.

When introduced into native ecosystems, various exotic Phytophthora species have proven to be serious to devastating pathogens. In California, native populations of the endangered endemics Ione manzanita, pallid manzanita, and Coyote ceanothus are threatened by Phytophthora root diaseases. Introduced root-rotting Phytophthora species have also caused decline and mortality of oaks, madrones, California bay and other woody natives in native stands. Sudden oak death, caused by the introduced pathogen P. ramorum, has caused extensive mortality of oaks and tanoaks in forests of the coast ranges from central California to southern Oregon.

Phytophthora species are serious pathogens of native vegetation, commercial forests, agricultural and horticultural crops, and cultivated landscapes worldwide. A disturbing recent trend has been the rapid dispersal of new Phytophthora species worldwide, facilitated by international movement of nursery stock and other plant material. These connections extend to California native plant nurseries. All of the detections of P. tentaculata in the US to date are in California native plant nurseries and restoration plantings. This pathogen was recently described and was previously known only from nursery and agricultural situations in Europe and China. It was ranked as a top-five priority threat by USDA in a recent review of Phytophthora species not present in the US. In 2016, P. quercina, the highest rated threat from this USDA analysis, was identified in a restoration planting on nursery-grown valley oaks (Quercus lobata) in Santa Clara County.

Diseases caused by both aerial and soil-borne Phytophthora species are common in plant nurseries. Plant nurseries provide nearly optimal environments for the development and spread of Phytophthora diseases. Production and dispersal of Phytophthora sporangia and swimming zoospores are favored by the wet and humid conditions found in nurseries. High root density within containers, close spacing of plants, plant handling, and frequent rearranging of containers all enhance opportunities for pathogen spread and reproduction.

Even with highly favorable conditions for disease development risk, Phytophthora diseases will not develop if the pathogen is not present. However, production practices in most nurseries provide many opportunities for Phytophthora introduction, through poor sanitation practices, using nonpasteurized potting media, reusing nonsanitized containers, or simply inadvertently buying infected (but possibly asymptomatic) plants from other sources. These unsafe practices have been facilitated by the widespread use of systemic fungicides that are active against Phytophthora. Using these chemicals in the nursery suppresses symptoms but does not eliminate these pathogens, allowing nurseries to sell infected plants that may appear healthy.

Unfortunately, it is often difficult to detect Phytophthora-infected plants in the nursery. Symptoms caused by aerial, foliar infecting species such as P. ramorum may be confused with symptoms of insufficient water or fertilizer burn. Root rot symptoms can be even harder to detect. Many drought-tolerant California natives will not show obvious above-ground symptoms under nursery conditions until root rot is severe (Figure 1). At earlier disease stages, healthy-appearing roots will still be present. Also, roots of many woody species are dark-colored, making it difficult to recognize infected roots.

Various tests can be used to detect and identify Phytophthora species associated with nursery plants. However, because of various logistical, cost, and test sensitivity issues, it is not currently practical to individually test large numbers of plants to reliably assess the infection status of each plant. Research is being conducted to develop fast and reliable methods for screening large numbers of plants for Phytophthora infections.

Phytophthora root rots have been as pervasive in California native plant nurseries as they are in horticultural plant nurseries. In a recent two year period, root-rotting Phytophthora species were detected at every California native plant nursery that was professionally sampled specifically to look for these pathogens. Many different plant species have tested positive for Phytophthora, including many that were not previously known to be Phytophthora hosts.

A long and growing list of Phytophthora species and likely hybrids (currently more than 25) have been detected in native plant nurseries in California, and over 50 species have been recovered from outplanted container stock. Multiple Phytophthora species have been found in many nurseries. Some detected species are relatively uncommon or not previously documented in California (e.g., P. tentaculata, P. quercina, ). Several previously undescribed Phytophthora species and hybrids have also been found in nursery-origin plant material that had been planted into restoration sites. Others (e.g., P. cinnamomi, P. cactorum, P. cambivora) are pathogens that have been associated with death and decline of cultivated plants in California for many years. Both ‘new’ and ‘older’ Phytophthora species are of concern because of their potential to permanently infest and spread from areas where they are introduced.

Figure 1. Shoots (top) and corresponding root systems (bottom) of three live nursery-grown toyons with Phytophthora root rot. All plants tested positive for P. cactorum, which attacks a wide range of woody plants. The foliage of the left plant was somewhat off-color and appeared water stressed; the plant had few, if any, live roots. The tall healthy-appearing plant on the right also had nearly complete root rot. The center plant, also healthy-appearing, had some apparently healthy roots on the outside of the root ball (upper center root image) , but most of the remaining roots were rotted (lower center root image). Pots had been reused and had various intact paper labels, suggesting that the pots had not been washed prior to reuse.

Infected nursery stock has been shown to be the source of various Phytophthora introductions. The pathogens that cause sudden oak death (P. ramorum) and Port Orford cedar root disease (P. lateralis) are among the better known introductions that have become widespread in parts of California, but recent research has demonstrated many more examples. In particular, we recently documented that a restoration planting conducted over 20 years ago in Santa Clara County was clearly associated with a widespread infestation involving multiple Phytophthora species in a mix of native hosts, including the endangered Ceanothus ferrisiae.

Most root-rotting Phytophthora infestations in native habitats have been detected because they cause decline and mortality of native species. They have been found in State Parks, public open space lands, botanical preserves, private properties, and elsewhere. The introduction of one or more virulent Phytophthora species can result in "sick" landscapes in which the most susceptible species suffer high levels of mortality and do not successfully regenerate. More tolerant species show reduced growth and vigor and may die during periods of drought or be attacked by opportunistic pest and pathogens. Ironically, many invasive weed species are unaffected by Phytophthora and may become more dominant in infested areas.

Continued introduction of exotic pathogenic Phytophthora species poses a significant threat to the conservation and sustainability of our native flora. Because there are limited options for managing Phytophthora diseases once they are established in native ecosystems, preventing introduction is of the utmost importance. Many of the most destructive Phytophthora species have wide host ranges and may persist in the soil for years after their hosts have been killed.

The principles of producing nursery plants that are free of these and other pests and pathogens can be summarized in five words: start clean, keep it clean. Phytophthora diseases cannot develop if these pathogens are not present. Though this sounds simple, it requires a diligent approach to:

This can be accomplished by using a systems approach to sanitation similar to the HACCP (hazard analysis and critical control point) systems that are used in food manufacturing to prevent contamination. Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Producing Clean Nursery Stock describes a systems approach toward nursery management that can consistently produce plants free of Phytophthora root rots as well as many other soil-borne diseases.

A key point of the systems approach is that is comprehensive. Many of the native plant nurseries where multiple Phytophthora species have been detected were using some of the best management practices (BMPs) that are part of a systems approach to clean plant production. However, these nurseries invariably failed to follow a complete systems approach, with predictably poor results. Plants cannot be “cured” of Phytophthora infections. Following selected BMPs on plant material that is already infected will not eliminate established Phytophthora infections and may not prevent spread. Conversely, plants that are initially clean can be contaminated by poor practices at many points during production.

A number of native plant nurseries have taken steps to adopt a complete systems approach, and work is underway to develop a certification system that would allow consumers to purchase clean native plants with confidence. Unfortunately, it will take some time to establish a certification process. In the meantime, some agencies have suspended the use of nursery stock for restoration projects and/or are developing or adopting specifications that would be used to certify plants that they purchase. The Working Group for Phytophthoras in Native Habitats has adopted Guidelines to Minimize Phytophthora Pathogens in Restoration Nurseries, which are based on the Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Producing Clean Nursery Stock.

A sizeable but unknown percentage of the existing native plant nursery inventory produced under conventional nursery practices is likely to be infected with a number of exotic Phytophthora species. These infections can eventually debilitate and kill infected plants after they are planted in the landscape. Beyond this, the pathogens can permanently infest sites where the plants were installed and then be spread unwittingly to other locations. Although it may be possible to identify and avoid some of the stock with the worst symptoms, it is not yet possible to identify all infected plants. This is the rather unfortunate situation that currently exists and has existed for years. Due to recent detections of P. tentaculata, P. quercina, and many other Phytophthora species associated with planted nursery stock, many organizations are now more aware of the extent and implications of this problem.

The spread of Phytophthora and other plant pathogens via infected nursery material is a long-established problem that cannot be solved quickly. It will take a sustained effort by many parties to assure that native plant nurseries are reliably clean systems. The industry is currently in a transitional phase in this effort and must work with restoration practitioners so the entire growing cycle is clean. Some native plant nurseries have undertaken substantial efforts to improve sanitation, but other nurseries have not yet acted or have not implemented enough changes to produce clean plants.

In the absence of certification standards and testing protocols, it is difficult to verify whether plants are free of Phytophthora. Nurseries may also be involved in CDFA’s voluntary clean nursery program. This is a positive step, but this program focuses on reducing rather than eliminating Phytophthora, and does not provide any guarantee that the nursery produces clean plants. Plants free of Phytophthora and other exotic pathogens and pests are requisite for habitat restoration; habitat is not being “restored” if long-lived exotic pathogens are being introduced with plantings. Public lands managers and others that have long-term stewardship responsibility over restored habitats have been among the first to support a verifiable clean plant certification system.

Bienapfl, J. C., and Balci, Y. 2014. Movement of Phytophthora spp. in Maryland’s nursery trade. Plant Dis. 98:134-144.

Brasier, C.M. 2008. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology 57(5):792-808.

Jung, T.; Orlikowski, L.; Henricot, B.; Abad-Campos, P.; Aday, A.G.; Aguín Casal, O.; Bakonyi, J.; Cacciola, S.O.; Cech, T.; Chavarriaga, D.; Corcobado, T.; Cravador, A.; Decourcelle, T.; Denton, G.; Diamandis, S.; Dogmus-Lehtijärvi, H.T.; Franceschini, A.; Ginetti, B.; Glavendekic, M.; Hantula, J.; Hartmann, G.; Herrero, M.; Ivic, D.; Horta Jung, M.; Lilja, A.; Keca, N.; Kramarets, V.; Lyubenova, A.; Machado, H.; Magnano di San Lio, G.; Mansilla Vázquez, P.J.; Marçais, B.; Matsiakh, I.; Milenkovic, I.; Moricca, S.; Nagy, Z.Á.; Nechwatal, J.; Olsson, C.; Oszako, T.; Pane, A.; Paplomatas, E.J.; Pintos Varela, C.; Prospero, S.; Rial Martínez, C.; Rigling, D.; Robin, C.; Rytkönen, A.; Sánchez, M.E.; Scanu, B.; Schlenzig, A.; Schumacher, J.; Slavov, S.; Solla, A.; Sousa, E.; Stenlid, J.; Talgø, V.; Tomic, Z.; Tsopelas, P.; Vannini, A.; Vettraino, A.M.; Wenneker, M.; Woodward, S.; and Peréz-Sierra, A. 2015. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. Forest Pathology. DOI: 10.1111/efp.12239.

Parke, J.L.; Knaus, B.J.; Fieland, V.J.; Lewis, C; Grünwald, N.J. 2014. Phytophthora community structure analyses in Oregon nurseries inform systems approaches to disease management. Phytopathology 104(10):1052-62.

Rooney-Latham, S.; Blomquist, C.; Swiecki, T.; Bernhardt, E.; Frankel, S.J. 2015. First detection in the USA: New plant pathogen, Phytophthora tentaculata, in native plant nurseries and restoration sites in California. Native Plants Journal 16:23-25.

Swiecki, T.J.; Bernhardt, E.; Garbelotto, M.; Fichtner, E. 2011. The exotic plant pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi: A major threat to rare Arctostaphylos and much more. In: Willoughby, J. W.; Orr, B. K.; Schierenbeck, K.A.; Jensen, N. J., eds. Proceedings of the CNPS 2009 Conservation Conference: Strategies and Solutions. Sacramento, CA: California Native Plant Society: 367–371. LINK

Yakabe, L. E., Blomquist, C. L., Thomas, S. L., and MacDonald, J. D. 2009. Identification and frequency of Phytophthora species associated with foliar diseases in California ornamental nurseries. Plant Dis. 93:883-890.