In most California forests, the P. ramorum spores that infect susceptible oak species (see Sidebar 1-1—Taxonomic Relationships between Susceptible Trunk Canker Hosts) are produced on the leaves of California bay (fig. 1-3) (Davidson and others 2005). However, oaks present in tanoak stands may be infected by spores produced on tanoak twigs.

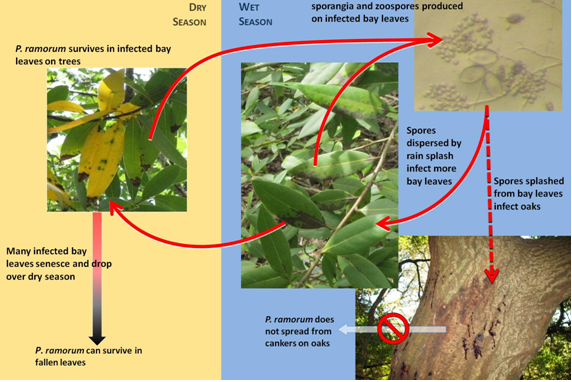

Figure 1-3—SOD disease cycle in oak-California bay forests where Phytophthora ramorum has become established. Phytophthora ramorum survives over the dry season primarily in infected bay leaves on trees. Sporulation occurs on bay leaves during the wet season, and rain-splashed spores initiate new leaf infections within the tree and on nearby bays. Under prolonged wet conditions, large amounts of spores build up in the canopy and are splashed onto nearby oaks (dashed arrow). Cankers develop on infected oak trunks but P. ramorum does not sporulate on trunk cankers.

P. ramorum causes dark lesions on California bay leaves, typically on downward-hanging leaf tips and leaf edges where water collects (fig. 1-3). The edge of the lesion is usually jagged rather than smooth and has a chlorotic (yellowish) border. Under wet and somewhat warm conditions (see Section 1.3.1. Environmental conditions), large quantities of sporangia and chlamydospores can be produced on infected leaves.

During the summer dry season, California bay leaves with P. ramorum infections commonly turn yellow (fig. 1-3) and drop earlier than healthy leaves. However, some infected leaves remain attached for at least a year. Consequently, P. ramorum can persist over the dry summer in the canopy of California bay.

Typically, the number of infected California bay leaves remaining in the canopy after the summer is relatively low, so few spores are produced during the first rains of the season in the fall and early winter. However, small numbers of spores can initiate new leaf infections on California bay. As the rainy season progresses, spores produced on infected leaves are splashed to other leaves where they start new infections. If rainfall is frequent, the number of foliar infections on California bay can increase explosively (Swiecki and Bernhardt 2008b). Peak P. ramorum spore production on California bay typically occurs when frequent rains occur in the spring, after temperatures have warmed up (Davidson and others 2005, 2008) (see Section 1.3.1. Environmental Conditions).

SOD in susceptible oaks is largely a byproduct of the P. ramorum foliar disease cycle on California bay. When conditions are favorable for foliar disease development in California bay, large numbers of spores from infected leaves are deposited on nearby oaks by dripping and splashing water. Water running down oak stems concentrates spores in the lower trunk area, where P. ramorum cankers typically develop (fig. 1-4). The lower trunk also tends to dry more slowly after rain. This provides an extended period of moisture, which favors P. ramorum spore germination and infection.

Figure 1-4—Phytophthora ramorum canker at the base of a coast live oak.

SOD is not known to spread from infected oaks to healthy oaks. P. ramorum does not produce sporangia on infected oak trunks; oaks are a "dead end" host for the pathogen (Davidson and others 2005) but see also section 3.1.3 Firewood. Leaf infection caused by P. ramorum develops uncommonly on oaks that are susceptible to trunk cankers (California black, coast live, Shreve, and canyon live oak). Because oak foliar infections are only seen in trees exposed to high spore loads from nearby infected California bay foliage, these occasional infected oak leaves have little or no role in pathogen spread.