Phytosphere

Research - Horticulture /

Urban Forestry /

Plant Resources / Agriculture

|

Management of Phytophthora ramorum (sudden oak death) in tanoak and oak stands |

| Cooperating researchers: |

|

|

Ted Swiecki and

Elizabeth Bernhardt

Phytosphere Research, Vacaville CA

email: phytosphere@phytosphere.com |

Matteo Garbelotto, Forest Pathology and Mycology Extension Specialist

Dept. of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley

http://nature.berkeley.edu/garbelotto/english/treatment.php |

Yana Valachovic - Forest Advisor

University of California Cooperative Extension - Humboldt and Del Norte Counties |

Project funding provided by:

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station

USDA Forest Service, State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection

updated June 2014

Landowners and managers have been seeking ways to protect coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), California black oak (Q. kelloggii), and tanoak (Notholithocarpus [=Lithocarpus] densiflorus) from Phytophthora ramorum, the pathogen that causes sudden oak death (SOD), both in newly-infested areas and areas that have been impacted by this disease for many years. Recent research has been used to formulate disease management strategies for minimizing the impacts of P. ramorum canker in susceptible stands of oaks and tanoak. However, data are needed to determine whether these management techniques will be effective when applied in the field at a practical scale.

In this collaborative project, we have established a network of long-term disease management plots to test the efficacy of the most promising techniques for managing P. ramorum canker in forests containing tanoak, coast live oak, and California black oak. Because disease epidemiology differs between different canker hosts, we are testing different control strategies in tanoaks and susceptible oaks, as described below. Results of this project will be used to improve disease management recommendations and will provide additional information on the epidemiology of the disease in treated and untreated stands.

Disease management in tanoak stands using potassium phosphite (Agrifos)

Managing SOD in tanoak stands is difficult because P. ramorum can complete its entire disease cycle on this host alone. P. ramorum causes leaf and twig infections in tanoak that lead to dieback of the fine twigs. UC Davis researchers in Dr. David Rizzo's lab have shown that P. ramorum also produces spores on infected tanoak twigs. These spores cause additional twig infections and, in sufficient numbers, can initiate bark cankers on the main stems of tanoak. These cankers can girdle and kill entire trees.

Application of phosphite to stem of a tanoak. A long spray wand is used so that the spray can be applied higher on the stem, where bark is thinner, to help increase uptake.

Application of phosphite to stem of a tanoak. A long spray wand is used so that the spray can be applied higher on the stem, where bark is thinner, to help increase uptake.

Potassium phosphite (also known as potassium phosphonate; trade name Agri-fos) is a selective, systemic fungicide with a high level of environmental safety and very low non-target toxicity (see box below). It has shown good levels of efficacy against P. ramorum canker in various trials. However, it has not been used widely enough in tanoak to determine the range of conditions under which it is effective. Furthermore, other questions remain as to the most effective way to utilize this material to manage P. ramorum canker in tanoak stands. Lab studies indicate that phosphite-treated tanoaks show resistance to artificial inoculations in the laboratory. Tanoaks that are treated with phosphite before being exposed to P. ramorum are less likely to develop stem cankers. Phosphite-treated tanoaks should also be less likely to develop the twig infections that produce spores. Treating blocks of tanoaks should therefore be more effective than treating scattered individual trees because the combination of these two effects (increased resistance to disease in plant tissues and reduced spore production) should provide a greater level of disease protection. In general, fungicidal materials such as phosphite typically work best when they are not exposed to very high disease pressure.

This study is testing whether phosphite is effective at reducing disease in tanoak when applied to a contiguous block of tanoaks. To account for possible regional differences, tanoak plots are distributed through much of the north to south range of P. ramorum in California’s Coast Ranges.

How safe are phosphites?

The fungicide we are testing in this study has the trade name Agri-fos. The active ingredients in Agri-fos are mono- and di-potassium salts of phosphorous acid. These salts are also referred to as phosphites or phosphonates. Phosphonates are considered by the EPA to be biopesticides. These salts are closely related to common substances that are found throughout the environment, though the phosphonate salts used for these fungicides are not naturally occurring (mineral) substances. Information on toxicity and environmental fate of The EPA fact sheet for this material is at http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_076002.htm. A key point in the EPA fact sheet is the following (see http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_076416.htm):

"ECOLOGICAL RISK ASSESSMENT

A potential for exposure exists to nontarget insects, fish, and other wildlife with foliar spray applications. However, test results indicate that the compound is practically nontoxic to birds and freshwater fish, and, at most, slightly toxic to aquatic invertebrates. Low toxicity, the proposed rate of application, and mitigating label language present minimal to nonexistent risk to wildlife."

Phosphorous acid and its ammonium, sodium and potassium salts are also exempt from food tolerance, for both crop and postharvest uses (see http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/fr_notices/frnotices_076002.htm). The EPA cited both the low toxicity of phosphonates and the fact that phosphonates have already been used widely as fertilizers in exempting phosphonates from tolerance. A preliminary study of tanoaks treated with Agri-Fos showed no evidence that the nutritional quality of the tanoak acorns was affected by this treatment (Meyers, Swiecki, and Mitchell, 2007).

Two major modes of action have been identified for phosphite. Phosphite increases the tree's natural resistance response to infection. This is generally thought to be the most important mode of action in many plants. In addition, at sufficiently high concentrations in the plant, phosphite itself is toxic to Phytophthora. Phosphite moves systemically in the tree and has a relatively long residual activity.

You can also view the master label (from the EPA label database (http://oaspub.epa.gov/pestlabl/ppls.home; the company number is 71962, product number is 1) and the MSDS for Agri-fos for more information. An important characteristic that can be found in the MSDS is that Agri-Fos is corrosive to most metals, a feature that we discovered when a brass pressure regulator was not adequately cleaned after spraying Agri-fos. We recommend the use of plastic or stainless steel sprayer components when using this material. |

Study progress to date (Phytosphere Research plots)

Methods

Plots treated in 2005 were established in cooperation with the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of Stewarts Point Rancheria under a project funded by USDA Forest Service, State and Private Forestry. We collected baseline observations on tree health and are reevaluating the trees periodically so that they can be compared with other plots that are part of this multi-location study.

All plots are close to or within areas where P. ramorum was present at the time plots were established. However, since the treatment is primarily preventative in nature, we selected study plot areas where all or almost all tanoaks were apparently free of trunk cankers. One difficulty in establishing this study was finding plot locations where trees were noninfected at the time of the original treatment but where trees were likely to be exposed to P. ramorum inoculum within a fairly short time after treatments had been initiated.

The Phytosphere tanoak plots are all dominated by tanoak, but most plots contain some conifers (Douglas-fir and/or coast redwood) and/or some madrone trees. California bay trees are not present in the plots. In a few plots, we removed small diameter bay trees at the onset of the study. P. ramorum spores are produced abundantly on infected bay leaves, and field studies and observations by various researchers have indicated that tanoaks adjacent to California bay trees have a very high risk of being infected and killed by P. ramorum. Since bay trees are not present in our plots, we are testing the efficacy of phosphite under conditions where it is most likely to be effective - in plots where tanoak is the primary source of P. ramorum spores and where all tanoaks in the plot have been treated with phosphite.

Although phosphite can be injected directly into tanoak trunks, in this study we are applying phosphite as a spray to the trunk. For this application, the phosphite solution is combined with a relatively high amount (2.5% by volume) of an organosilicate surfactant (trade name Pentrabark), as specified by the Agri-fos label. The trunk spray application allows one to treat a larger number of trees in a shorter time compared to trunk injection, so the spray method is more suited to treating large numbers of trees. We have used both an ATV-mounted sprayer and an electric backpack sprayer mounted on a custom cargo bicycle to apply calibrated amounts of spray solution to the treated trees.

The ATV-mounted sprayer is especially useful for sites with large overall spray volumes, but sites need to be fairly level and clear in the understory.

We use a modified mountain bike to hold a Shurflo PropackTM electric backpack sprayer. Additional containers with water and spray solution can be attached to the bike when it is pushed (not ridden) to the application site. The bike sprayer can be used in fairly steep plots and can be negotiated around material in the understory fairly easily. It is also less fatiguing to the applicator than wearing the backpack, and allows more freedom of movement.

For both types of sprayers, we used custom-made telescoping spray booms that allowed us to apply the spray high on the trunk - up to a height of about 20 ft (6 m) (top photo; details of the construction of the high reach spray wand are available from this link). Applying the spray high on the trunk provides two main advantages that should increase phosphite uptake:

1. Material is applied where the bark is thinner (and more permeable) and generally less densely coated with mosses that may absorb and tie up the phosphite.

2. As the residue is rewetted by rain and is washed down the stem, it has additional opportunities to be absorbed in the lower portion of the stem, rather than being washed into the soil where it would be largely unavailable for uptake by the tree.

We use TeeJet air induction nozzles to provide relatively large spray droplets and minimize drift. Nonetheless, some overspray and drift is inevitable. One disadvantage of the trunk application method is that the spray solution is quite phytotoxic to tanoak foliage (photo), and leaves that are wetted by the spray solution become scorched or are completely killed. Hence, stem application is impractical for small understory tanoaks because the overspray will kill much of the foliage.

Leaf scorching on these tanoak leaves is due to overspray and drip of Agri-fos / Pentrabark spray solution onto the foliage. This photo was taken in January 2006, about 1 month after the spray application.

While it is impractical to treat very small understory tanoaks, these seedlings and saplings may still serve as a

source of P. ramorum spores. Therefore, in our treatment protocol, small understory tanoaks (less than about about 3 inch diameter), if present, are cut down and removed from the phosphite-treated and control plots. In the two locations where we removed a significant amount of understory tanoak, we set up a second control plot with no

understory tanoak removal. The plots without understory tanoak removal are included as a check to determine whether removal of understory tanoaks alone can affect disease development within the plot.

We are currently using a spray program that includes two applications the first year (winter and spring), followed by annual reapplication. The reapplication interval may be extended later in the study if the one-year reapplication interval is shown to be effective.

Results and observations

The most recent results can be found here

Phytotoxicity. As expected, Agri-fos / Pentrabark caused phytotoxicity on foliage that received overspray. We have seen necrosis (tissue death) on tanoak and redwood foliage as well as on mosses growing on the stem surfaces that were thoroughly wetted by the spray solution. In most cases, exposed woody twigs were not killed. New shoots have formed from buds on twigs that were defoliated due to phytotoxicity. However, some small diameter understory stems that were retained in some plots appear to have been killed as the result of Agri-fos phytotoxicity. These trees have had severe phytotoxicity affecting the majority of their foliage in successive years. This result supports our study design concept of removing rather than spraying small understory tanoaks.

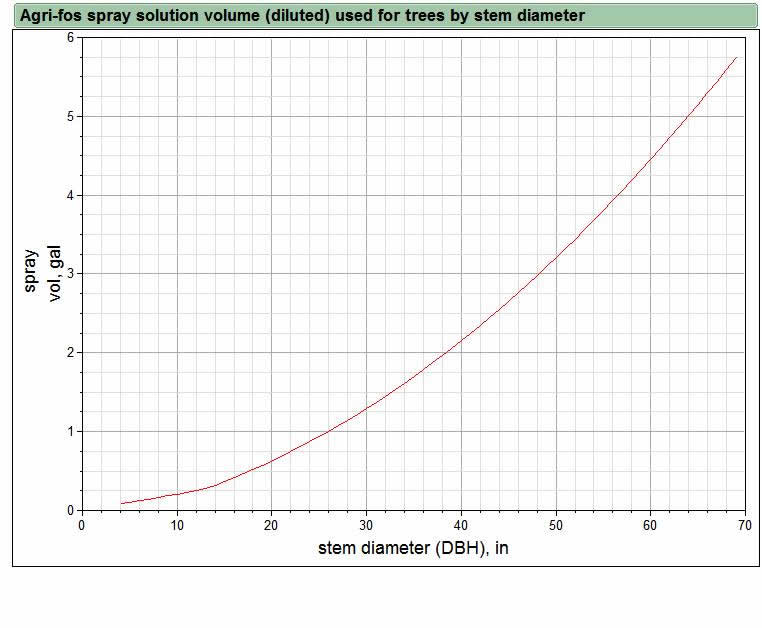

Application amount and cost. To treat the original 256 live stems in the 5 sprayed plots described above required 39 gal (148 L) of spray solution. This volume of spray solution contains about 19 gallons (72 L) of Agrifos and 1 gallon (3.7 L) of Pentrabark. The average diameter (DBH) of all stems in the treated plots was 6.75 inches (17 cm), with a range from about 3 inches (8 cm) to about 35 inches (89 cm). The spray volume used per stem was modest for small diameter trees (e.g., about 1 pint [473 ml] for a 6 inch [15 cm] diameter stem). However, for larger stems, the spray volume was much more substantial because the spray volume curve we used (graph) was calculated by averaging the linear rate based on stem surface area and the power curve rate based on stem volume. For a 30 inch diameter stem, the spray volume applied would be 1.3 gal (4.9 L). This is more than 10 times the volume applied to the 6 inch stem, even though the diameter is only 5 times that of the smaller stem.

Put another way, 5 gal of mixed spray solution would treat about 40 6-inch diameter stems, but would be a bit short of the amount needed to treat four 30-inch diameter stems. At current full retail prices for Agri-fos and Pentrabark (variable, but about $200 for 5 gal of mixed spray solution=2.5 gal Agri-fos and 1 pint Pentrabark) the cost of materials alone for each stem would range from about $5 (6 inch stem) to over $50 (30 inch stem) for each application. If the chemicals can be purchased at closer to wholesale cost, the cost per tree will be substantially lower.

Above graph shows the targeted amount of diluted Agri-fos spray solution used for treated stems by stem diameter at breast height (DBH). For trees less than 12 inches DBH, we use a linear function to calculate spray volume based on diameter. For stems 12 inches DBH or larger, a quadratic term is added to the equation, resulting in the curvilinear relationship seen in the graph. The quadratic formula helps keep the ratio of Agri-fos applied per unit stem volume relatively constant.

Disease management in coast live oak and California black oak using selective removal and/or pruning of California bay |

|

The small understory bay to the left of this coast live oak was the source of the P. ramorum spores that killed the oak. |

|

Disease epidemiology in coast live oaks and California black oaks differs from that in tanoaks because the pathogen, P. ramorum, has not been shown to sporulate to any significant degree on either oak. Several lines of research indicate infections on these oaks are usually initiated by spores that are produced on infected California bay leaves. Recent research indicates that most of the disease risk in oaks is associated with bay that are quite close to or actually overtopping the oak trunk. This study investigates whether selective removal of bay from this localized zone near the oak trunk is sufficient to reduce disease risk to an acceptably low level. To date, only Phytosphere Research has established plots for this portion of the study.

Methods

This study is based on matched pairs of SOD-susceptible oaks (coast live or California black oak). The trees within the pairs were matched to the degree possible for known factors that influence disease risk, especially the amount of bay in the immediate vicinity of the trunk. One tree of each pair was designated as the control and the bay surrounding it was not altered. For the other (treated) tree, we removed bay from the zone nearest to the trunk. For these trees, we attempted to achieve a minimum clearance of 8 ft (2.5 m) of horizontal distance between bay foliage and the oak trunk. Clearance is measured by projecting a vertical line down from the nearest bay foliage to the trunk and measuring the horizontal distance to the oak trunk from that line. Where it could be achieved without excessive effort, the clearance was increased up to about 16 ft (5 m), especially in the direction of the prevailing storm winds (generally south and west of the tree). Clearance was obtained by removing small-diameter bay stems close to the oak and/or bay branches from bays located farther from the oak. Oak trees were not pruned; the bay-oak clearance was obtained only through removal or pruning of bay. The box below summarizes lists the overall criteria that were used for clearing bay around treated trees .

Guidelines for bay removal to reduce risk of SOD in oaks

- Clear bay minimum of 8 ft (2.5 m) from trunk (distance from bay foliage to oak trunk).

-

Remove bay to 16 ft (5 m) if feasible, especially to S and W of oak trunk.

-

Where complete bay removal is difficult to obtain in the 8 to 16 ft (2.5-5 m) distance range, remove low bay canopy by pruning low branches.

-

Remove understory bay seedlings within 6.5 ft (2 m) of stem.

-

Keep cut bay foliage at least 3 ft (1 m) away from oak stems.

-

Cut stems of poison oak climbing into the canopy of the oak or adjacent trees if within 8 ft (2.5 m). |

Locations used in this study are in Sonoma, Napa, and Solano Counties in areas where P. ramorum is present and causing symptoms on bay and usually at least some oaks. Because localized bay removal is primarily a preventive treatment, oaks selected for the study were generally free of obvious stem cankers. However, we included nine trees with small cankers in the study to assess whether disease progress could be slowed by reducing the amount of additional inoculum that lands on already-infected trees.

Bay removal treatments were initiated in spring 2007. To date, 31 coast live oak pairs and 18 California black oak pairs have been established, each pair consisting of matched control and treated (bay removal) trees. Many trees in the study have multiple trunks, each of which is tracked separately for data collection anad analysis. Study trees are assessed annually for SOD symptoms. We are also evaluating the amount of regrowth that occurs from cut bay stumps. None of the bay stumps in this study were treated with herbicides to prevent resprouting.

To minimize the costs associated with felling/pruning and the handling of downed material, we generally selected oaks that required relatively little bay removal to make a large change in disease risk. Ideal oaks for treatment are those with only one to a few small diameter understory bays near the trunk. These situations commonly occur where bay is not the dominant tree in the stand. The largest diameter bay stem we removed was about 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter. However, bay stems typically flare widely at the base, so the basal cut is typically much larger than the DBH of the felled stem. Even small diameter bays are commonly quite tall. In dense stands, felled bay stems may hang up in the canopies of other trees and can be time consuming to drop.

At most study locations, downed material was left on site. We disposed of cut material using "lop and scatter": material was cut into relatively short lengths and spread out to avoid forming piles. We kept cut bay foliage at least 3-6 ft (1-2 m) away from the trunks of susceptible oaks. Splash dispersal of most P. ramorum inoculum from bay foliage near the ground is generally likely to be limited to about 3 ft (1 m) or less. Depending on weather conditions and exposure to sunlight, cut bay foliage can dry out within a few days to weeks. In heavily shaded stands during cool, wet conditions, bay foliage can remain green (and potentially a source of P. ramorum inoculum) for at least a month. Hence, at least during the rainy season, we believe it is prudent to keep cut bay foliage away from susceptible oak trunks until the bay foliage has become completely desiccated.

|

|

| Coast live oak prior to removal of bay (at left); foliage of the bay overhangs the oak trunk. |

Same tree after bay removal. Note bay stump on left side of photo. The distance between the nearest bay leaf and the oak trunk for the tree in the center of the picture has been increased to more than 16 ft (5 m). |

We collected baseline observations on tree health prior to treatment and are reevaluating the trees periodically. We also measured the minimum oak trunk-bay foliage horizontal distance and assessed bay cover within concentric zones near the oaks prior to the study and after bay removal for the treated trees.

Spore monitoring in plots. During the spring of 2007, we monitored spore dispersal near the trunks of treated (bay removal) and control trees at two study locations using buckets containing bay leaf baits as noted for the tanoaks above. In 2010, we used the sand-based spore traps discussed above to sample spores at Annadel SP plots.

Results and observations

Spore monitoring in plots. As noted for the tanoak plots above, we did not detect any P. ramorum on bay leaf baits from any of the sampling buckets around control or treated trees in 2007 (photo). As with the tanoak plots, rainfall measured in plots was low during the monitoring period (beginning of April through mid May). Rainfall amounts in the first 3 weeks of April were 1.6 and 2.4 inches beneath tree canopy at the two locations. In the following three week period, we recorded 0.3 and 0.5 inch of rainfall through the canopy. The low rainfall in spring 2007 was generally unfavorable for P. ramorum sporulation in much of northern California. Because rainfall in spring 2008 and spring 2009 was even more sparse than in 2007, we did not repeat the P. ramorum monitoring in 2008 or 2009.

Phytophthora ramorum spores were detected using leaf baits floating in water in plastic buckets. Higher amounts of infection are seen in the leaf baits as the amount of P. ramorum spores falling in the bucket increases. However, no infected leaf baits were detected in the spring 2007 monitoring. For oaks, two buckets were placed near the north and south sides of the trunk. Note the sprouting bay stump behind the left bucket and dead bay foliage from the cut stems in the background.

In 2010, we used sand spore traps to assess inoculum deposition near study trees at Annadel State Park over two time intervals (3/26-4/22 and 4/22-6/3). Traps were set up adjacent to trunks of four trees from which bay had been removed and four control trees which had not had any bay removal. All control traps were located under bay canopy, whereas the traps near the bay removal trees were 3 to 5.8 m from bay canopy. The first time interval at Annadel was the same as used for the FE tanoak plots. At Annadel, 3.7 inches of rain fell during the first time increment. No P. ramorum inoculum was detected in this initial round of trapping. In addition, bay foliar symptoms were not observed in the vicinity of the traps when they were deployed (3/26/10) or picked up (4/22/10).

We set out four fresh spore traps on 22 April 2010 around two pairs of trees that were in a portion of the study area that had greater bay cover and more SOD overall. Over the interval from 4/22-6/3, we measured 2 inches of rainfall under the trees. When the traps were removed on 3 June 2010, bay leaves around one of the control trees had developed extensive foliar necrosis due to P. ramorum infection. We detected P. ramorum from the spore trap under this bay. The spore traps adjacent to oaks from which bay had been removed were negative, as was the spore trap adjacent to a noncleared oak in which the bay was nonsymptomatic. These results indicate that rainfall was sufficient for P. ramorum to initiate infections and produce spores on some bay trees, but weather conditions were not extreme enough to result in widespread infection of bays.

Sand spore trap (center) under bay foliage . Water that falls into the tray is channeled through a sand-filled column that retains P. ramorum spores. Note that bay canopy (bay trunk is next to bucket) overhangs the main stems of the oak (to left of spore trap).

Efficacy. Results through June 2013 can be found here

Bay regrowth. Bay stumps can be treated with herbicides immediately after cutting to inhibit subsequent sprouting. In this study, cut bay stumps were not treated, which allows us to assess how fast sprouts regrowth and how often follow up treatments would be needed if herbicides are not used. Results through June 2013 can be found here

Nondiscrimination Statement

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

|