Disease management in tanoak stands using potassium phosphite (Agrifos)

Managing SOD in tanoak stands is difficult because P. ramorum can complete its entire disease cycle on this host alone. P. ramorum causes leaf and twig infections in tanoak that lead to dieback of the fine twigs. UC Davis researchers in Dr. David Rizzo's lab have shown that P. ramorum also produces spores on infected tanoak twigs. These spores cause additional twig infections and, in sufficient numbers, can initiate bark cankers on the main stems of tanoak. These cankers can girdle and kill entire trees.

Potassium phosphite (also known as potassium phosphonate; trade name Agri-fos) is a selective, systemic fungicide with a high level of environmental safety and very low non-target toxicity (see box below). It has shown good levels of efficacy against P. ramorum canker in various trials. However, it has not been used widely enough in tanoak to determine the range of conditions under which it is effective. Furthermore, other questions remain as to the most effective way to utilize this material to manage P. ramorum canker in tanoak stands. Lab studies indicate that phosphite-treated tanoaks exhibited higher levels of resistance to artificial inoculations in the laboratory. Tanoaks that are treated with phosphite before being exposed to P. ramorum are less likely to develop stem cankers. In addition, phosphite-treated tanoaks should be less likely to develop the twig infections that produce spores. Treating blocks of tanoaks should therefore be more effective than treating scattered individual trees because the combination of these two effects (increased resistance to disease in plant tissues and reduced spore production) should provide a greater level of disease protection. In general, fungicidal materials such as phosphite typically work best when they are not exposed to very high disease pressure.

This study will test how effective phosphite is at reducing disease in tanoak when applied to a contiguous block of tanoaks. To account for possible regional differences, tanoak plots are distributed through much of the north to south range of P. ramorum in California’s Coast Ranges.

How safe are phosphites?

The fungicide we are testing in this study has the trade name Agri-fos. The active ingredients in Agri-fos are mono- and di-potassium salts of phosphorous acid. These salts are also referred to as phosphites or phosphonates. Phosphonates are considered by the EPA to be biopesticides. These salts are closely related to common substances that are found throughout the environment, though the phosphonate salts used for these fungicides are not naturally occurring (mineral) substances. Information on toxicity and environmental fate of The EPA fact sheet for this material is at http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_076002.htm. A key point in the EPA fact sheet is the following (see http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_076416.htm):

"ECOLOGICAL RISK ASSESSMENT

A potential for exposure exists to nontarget insects, fish, and other wildlife with foliar spray applications. However, test results indicate that the compound is practically nontoxic to birds and freshwater fish, and, at most, slightly toxic to aquatic invertebrates. Low toxicity, the proposed rate of application, and mitigating label language present minimal to nonexistent risk to wildlife."

Phosphorous acid and its ammonium, sodium and potassium salts are also exempt from food tolerance, for both crop and postharvest uses (see http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/fr_notices/frnotices_076002.htm). The EPA cited both the low toxicity of phosphonates and the fact that phosphonates have already been used widely as fertilizers in exempting phosphonates from tolerance. A preliminary study of tanoaks treated with Agri-Fos showed no evidence that the nutritional quality of the tanoak acorns was affected by this treatment (Meyers, Swiecki, and Mitchell, 2007).

Two major modes of action have been identified for phosphite. Phosphite increases the tree's natural resistance response to infection. This is generally thought to be the most important mode of action in many plants. In addition, at sufficiently high concentrations in the plant, phosphite itself is toxic to Phytophthora. Phosphite moves systemically in the tree and has a relatively long residual activity.

You can also view the master label (from the EPA label database (http://oaspub.epa.gov/pestlabl/ppls.home; the company number is 71962, product number is 1) and the MSDS for Agri-fos for more information. An important characteristic that can be found in the MSDS is that Agri-Fos is corrosive to most metals, a feature that we discovered when a brass pressure regulator was not adequately cleaned after spraying Agri-fos. We recommend the use of plastic or stainless steel sprayer components when using this material. |

Study progress to date (Phytosphere Research plots)

Methods

Plots treated in 2005 were established in cooperation with the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of Stewarts Point Rancheria under a project funded by USDA Forest Service, State and Private Forestry. Though this project, we are collecting additional data in these plots so that they can be compared with other plots that are part of this multi-location study.

All plots are close to or within areas where P. ramorum was present at the time plots were established. However, since the treatment is primarily preventative in nature, we selected study plot areas where all or almost all tanoaks were apparently free of trunk cankers. One difficulty in establishing this study was finding plot locations where trees were noninfected at the time of the original treatment but where trees were likely to be exposed to P. ramorum inoculum within a fairly short time after treatments had been initiated.

The Phytosphere tanoak plots are all dominated by tanoak, but most plots contain some conifers (Douglas-fir and/or coast redwood) and/or some madrone trees. California bay trees are not present in the plots. In a few plots, we removed small diameter bay trees at the onset of the study. P. ramorum spores are produced abundantly on infected bay leaves, and field studies and observations by various researchers have indicated that tanoaks adjacent to California bay trees have a very high risk of being infected and killed by P. ramorum. Since bay trees are not present in our plots, we are testing the efficacy of phosphite under conditions where it is most likely to be effective - in plots where tanoak is the primary source of P. ramorum spores and where all tanoaks in the plot have been treated with phosphite.

Although phosphite can be injected directly into tanoak trunks, in this study we are applying phosphite as a spray to the trunk. For this application, the phosphite solution is combined with a relatively high amount (2.5% by volume) of an organosilicate surfactant (trade name Pentrabark), as specified by the Agri-fos label. The trunk spray application allows one to treat a larger number of trees in a shorter time compared to trunk injection, so the spray method is more suited to treating large numbers of trees. We have used both an ATV-mounted sprayer and an electric backpack sprayer mounted on a custom cargo bicycle to apply calibrated amounts of spray solution to the treated trees.

|

| The ATV-mounted sprayer is especially useful for sites with large overall spray volumes, but sites need to be fairly level and clear in the understory. |

|

| We use a modified mountain bike to hold a Shurflo PropackTM electric backpack sprayer. Additional containers with water and spray solution can be attached to the bike when it is pushed (not ridden) to the application site. The bike sprayer can be used in fairly steep plots and can be negotiated around material in the understory fairly easily. It is also less fatiguing to the applicator than wearing the backpack, and allows more freedom of movement. |

For both types of sprayers, we used custom-made telescoping spray booms that allowed us to apply the spray high on the trunk - up to a height of about 20 ft (6 m) (top photo; details of the construction of the high reach spray wand are available from this link). Applying the spray high on the trunk provides two main advantages that should increase phosphite uptake:

1. Material is applied where the bark is thinner (and more permeable) and generally less densely coated with mosses that may absorb and tie up the phosphite.

2. As the residue is rewetted by rain and is washed down the stem, it has additional opportunities to be absorbed in the lower portion of the stem, rather than being washed into the soil where it would be largely unavailable for uptake by the tree.

We use TeeJet air induction nozzles to provide relatively large spray droplets and minimize drift. Nonetheless, some overspray and drift is inevitable. One disadvantage of the trunk application method is that the spray solution is quite phytotoxic to tanoak foliage (photo), and leaves that are wetted by the spray solution become scorched or are completely killed. Hence, stem application is impractical for small understory tanoaks because the overspray will kill much of the foliage.

|

| Leaf scorching on these tanoak leaves is due to overspray and drip of Agri-fos / Pentrabark spray solution onto the foliage. This photo was taken in January 2006, about 1 month after the spray application. |

While it is impractical to treat very small understory tanoaks, these seedlings and saplings may still serve as a

source of P. ramorum spores. Therefore, in our treatment protocol, small understory tanoaks (less than about about 3 inch diameter), if present, are cut down and removed from the phosphite-treated and control plots. In the two locations where we removed a significant amount of understory tanoak, we set up a second control plot with no

understory tanoak removal. The plots without understory tanoak removal are included as a check to determine whether removal of understory tanoaks alone can affect disease development within the plot.

We are currently using a spray program that includes two applications the first year (winter and spring), followed by annual reapplication. The reapplication interval may be extended later in the study if the one-year reapplication interval is shown to be effective. If funding is continued, we expect to observe these plots for at least 3 years.

During the spring of 2007, we monitored spore production within the plots using buckets containing bay leaf baits. In spring 2008 we monitored spore production by collecting soil samples and using rhododendron leaf disks to bait the samples for P. ramorum. We also collected baseline observations on tree health and are reevaluating the trees periodically. In June 2008, we also collected leaf samples that were assayed for disease resistance by the Garbelotto lab.

Results and observations to date (12/09)

Phytotoxicity. No adverse effects have been noted as the result of the Agri-fos / Pentrabark application other than the expected phytotoxicity seen on sprayed foliage. We have seen necrosis (tissue death) on tanoak and redwood foliage as well as on mosses growing on the stem surfaces that were thoroughly wetted by the spray solution. However, exposed woody twigs were not killed; new shoots have formed from buds on twigs that were defoliated due to phytotoxicity.

Spore monitoring in plots. Our 2007 monitoring of spore production in study plots from the beginning of April through mid-May confirmed that weather conditions in spring 2007 were unfavorable for P. ramorum spore production. We did not detect any P. ramorum on bay leaf baits in any of the tanoak plots. Rainfall measured in plots was low during this period. Rainfall amounts in the first 3 weeks of April were about 1 to 2 inches (2.5-5.8 cm) in the plots, but in the following three week period, less than 0.5 inch (0.13-0.4 cm) was recorded.

Results from the spring 2007 spore monitoring are consistent with those of other researchers sampling in northern California during this period. The overall lack of P. ramorum spore production in the plots does not allow us to determine whether spore production was affected by the Agri-fos treatment. However, it does suggest very few or no new infections in the plots would have been likely to occur in spring 2007. Hence, trees that have shown trunk symptoms for the first time in 2007 were almost certainly infected in previous years. Monitoring by researchers in Dr. David Rizzo's lab (UC Davis) has indicated that the spring of 2005 and especially 2006 were favorable for P. ramorum spore production.

Rainfall in spring 2008 and 2009 was also very low; little or no measurable precipitation fell in the study areas over the intended baiting period in this record drought year. We therefore used soil baiting rather than the floating bay leaf baits to monitor spore production in the plots. Soil baiting detects P. ramorum inoculum that has been washed into the soil, and has the potential to detect inoculum deposited earlier in the rainy season. These tests were conducted by Dr. Elizabeth Fitchner in Dr. Dave Rizzo's lab at UC Davis. No P. ramorum was detected in any of the soil samples. This indicates that very few spores were produced in the plots in early 2008 and 2009 irrespective of the treatment (Agrifos or control). Dry soil and warm temperatures through most of the spring of 2008 and 2009 may also have reduced the survival of any inoculum that washed into the soil during the short rainy season.

Efficacy. Monitoring disease development on tanoaks within the study plots is our main method for determining whether the Agri-fos treatment is effective. We assessed the disease status of each tanoak stem in the plots prior to the start of the study and are periodically reassessing the stems to detect evidence of disease. The plots that were established in the winter of 2005/2006 have the now been observed for 4 years since the start of the experiment. Likely symptoms of P. ramorum canker were noted in one of these two locations (SF) within the first 6 months of the study, and trees killed by P. ramorum were present in some of the plots by 1.5 years after the start of the study. At the other location (BL), likely P. ramorum cankers were not noted until 1.5 years after the start of the study. Levels of disease in these two locations are summarized in the table below.

Plot |

Treatment |

live stems at start of study (12/05) |

% of stems with likely P. ramorum canker in 6/08 |

% of stems with likely P. ramorum canker in 6/09 |

BL3 |

Agri-Fos+thin |

57 |

0 |

1.8% |

BL4 |

thinned control |

57 |

1.8% |

1.8% |

BL5 |

nonthinned control |

55 |

5.5% |

7.1% |

SF1 |

Agri-Fos+thin |

63 |

23.8% |

27% |

SF2 |

thinned control |

61 |

11.5% |

13.1% |

SF6 |

nonthinned control |

72 |

15.3% |

16.7% |

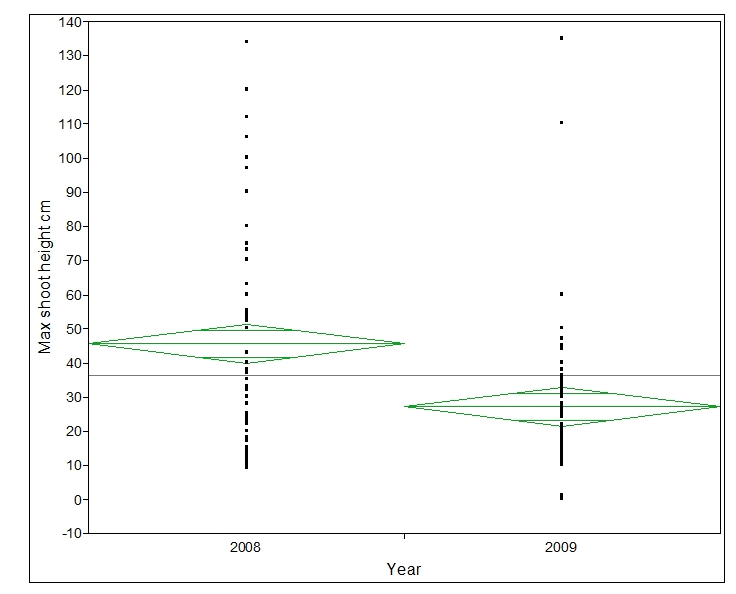

Overall disease levels in all plots are much higher at the SF location than at the BL location. Plot SF1 (Agri-Fos treated) had the highest incidence of disease overall, but because this plot is also closest to the original P. ramorum disease center at this location, it is possible that many of the symptomatic trees in this plot had cankers at the start of the study that were not yet detectable in a visual inspection. Cankers on tanoak are often cryptic and may not produce visible external symptoms (such as bleeding) until the disease is very advanced; small-diameter trees may actually be killed without developing bleeding cankers. Given the negligible spore production in the plots in spring 2007, 2008, and 2009, it is likely that most disease symptoms in the SF plots resulted from infections initiated in the spring of 2006 or 2005. If this is the case, the data would indicate that phosphite application is ineffective at preventing disease progress in tanoaks that are already infected. Various researchers have noted that phosphite is most likely to be effective when applied as a protectant to uninfected plants; it is generally much less successful at limiting established infections.

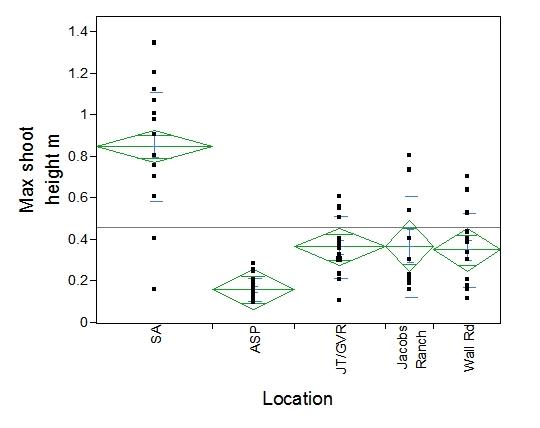

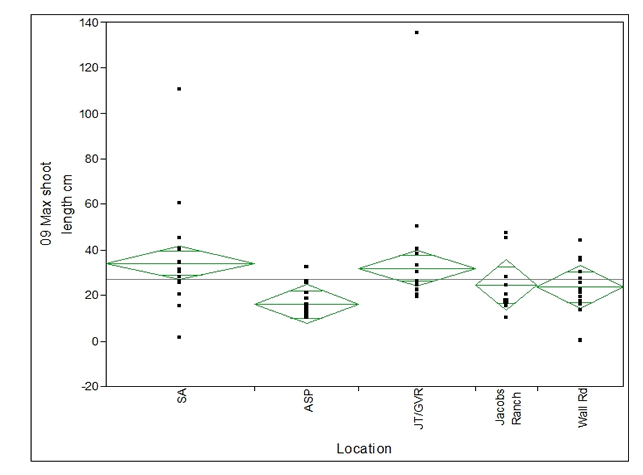

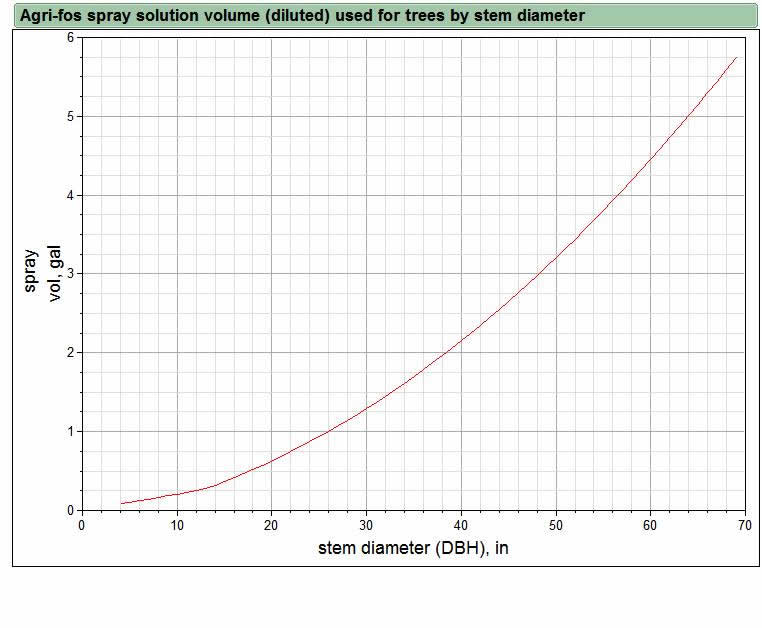

For all of the SF plots, the mean diameter of trees with P. ramorum symptoms in June 2008 was significantly greater than the diameter of asymptomatic trees. Furthermore, 5 of the 7 stems killed by P. ramorum in the Agri-Fos plot SF1 had stem diameters greater than 15 inches (38 cm). This raises the possibility that the apparent lack of efficacy in plot SF1 could be due to phosphite concentrations in the treated trees: the larger-diameter stems might not have received a high enough dose of phosphite to provide adequate levels of disease protection. Although the surface area of the trunk increases in a linear fashion with increasing stem radius or diameter, the volume of bark and sapwood tissue increases as a function of the square of the radius. Hence, large-diameter trees receive proportionately less phosphite per unit stem volume than do small diameter trees when sprayed according to the standard label recommendation. In our plots, we have been using a spray volume that has been calculated to reduce this disparity (see graph below), but it is not possible to completely correct for this effect in large-diameter trees because only a limited amount of spray volume can be adsorbed onto the bark surface. Additional data on disease development in these plots and results from leaf bioassays of treated trees should allow us to determine whether the efficacy of the treatment is affected by stem diameter. (see our Dec 2007 progress report for a full discussion about stem diameter and application rate).

The plots at the BL location were further from an active P. ramorum disease center at the time that the study was started. Disease levels at this location are still very low, but symptomatic trees have only been seen in the control plots to date. It is still too early to tell if this is an indication that the Agri-Fos treatment is working. At the other locations that were initially treated in Jan/Feb 2007, there has been little change in disease levels in the plots since they were established, presumably due to the fact that disease pressure has been low since the plots were established.

Bioassay to test for phosphite activity in leaves. In June 2008, we collected leaf samples from Agrifos-treated and control tanoaks for a bioassay conducted by the Garbelotto lab. In the assay, P. ramorum inoculum is applied to the petiole end of detached leaves, and the length of the resulting lesion is measured. This assay has been used previously to show effects of phosphite application, and we had hoped to use it to get an early indication of whether the Agrifos treatments were having an effect in treated plots and to look at relationships between phosphite activity and stem diameter. Results from the assay failed to show any average difference in lesion development between trees from treated and control plots. In fact, the only significant relationship in the data was a correlation between leaf size and lesion development. Data from the assay were also highly variable. At this point, it appears that the assay did not perform this year as it had in the past and appears to be sensitive to leaf size and/or maturity.

Application amount and cost. To treat the original 256 live stems in the 5 sprayed plots described above required 39 gal (148 L) of spray solution. This volume of spray solution contains about 19 gallons (72 L) of Agrifos and 1 gallon (3.7 L) of Pentrabark. The average diameter (DBH) of all stems in the treated plots was 6.75 inches (17 cm), with a range from about 3 inches (8 cm) to about 35 inches (89 cm). The spray volume used per stem was modest for small diameter trees (e.g., about 1 pint [473 ml] for a 6 inch [15 cm] diameter stem). However, for larger stems, the spray volume was much more substantial because the spray volume curve we used (graph) was calculated by averaging the linear rate based on stem surface area and power curve rate based on stem volume. For a 30 inch diameter stem, the spray volume applied would be 1.3 gal (4.9 L). This is more than 10 times the volume applied to the 6 inch stem, even though the diameter is only 5 times that of the smaller stem.

Put another way, 5 gal of mixed spray solution would treat about 40 6-inch diameter stems, but would be a bit short of the amount needed to treat four 30-inch diameter stems. At current full retail prices for Agri-fos and Pentrabark (variable, but about $200 for 5 gal of mixed spray solution=2.5 gal Agri-fos and 1 pint Pentrabark) the cost of materials alone for each stem would range from about $5 (6 inch stem) to over $50 (30 inch stem) for each application. If the chemicals can be purchased at closer to wholesale cost, the cost per tree will be substantially lower.

Above graph shows the targeted amount of diluted Agri-fos spray solution used for treated stems by stem diameter at breast height (DBH). For trees less than 12 inches DBH, we use a linear function to calculate spray volume based on diameter. For stems 12 inches DBH or larger, a quadratic term is added to the equation, resulting in the curvilinear relationship seen in the graph. This curve helps keep the ratio of Agri-fos applied per unit stem volume relatively constant. |